Building multi-agent customer support with Strands Agents TypeScript SDK and Amazon Bedrock

Build a multi-agent customer support system on Amazon Bedrock using the Strands Agents TypeScript SDK. Ticket triage, routing, and escalation detailed.

The Strands Agents TypeScript SDK lets you build multi-agent AI systems on Amazon Bedrock using typed tool definitions with Zod, async iterator streaming, and a model-driven agent loop. I used it over a weekend to build a customer support system where a triage agent classifies incoming tickets, routes them to specialist agents (billing, technical, account management), and escalates to a human when things go sideways. The whole thing runs on Claude Sonnet via Bedrock. It took about 14 hours across Saturday and Sunday. At least 4 of those hours were me fixing problems I caused. This post covers the architecture, the four things that broke, and what you'd need to change to put something like this in production. The full source code is on GitHub.

Why customer support, and why TypeScript?

I wanted to build something with agentic AI that wasn't a toy. Not another "summarize this PDF" demo, but a system that has to make real decisions: figure out what kind of problem a customer has, pick the right specialist, know when to give up and hand off to a human. Customer support works well for this because the requirements are genuinely multi-step. You need to understand the problem, look up data, decide on an action, and handle edge cases without embarrassing yourself.

I went with TypeScript specifically because almost nobody has written about it yet. The Strands Python SDK has been around since May 2025 and has good coverage: multi-agent with GraphBuilder, Swarm orchestration, the whole package. But AWS announced TypeScript support in preview in December 2025, and blog posts about building real things with it are basically nonexistent. I wanted to find out where the walls are.

Short version: the core agent loop is more capable than I expected. The multi-agent story requires manual wiring. Both of those things turned out to be interesting.

How is agentic AI different from a chatbot?

A regular chatbot takes your input, sends it to an LLM, and returns whatever comes back. One round trip. An agentic AI system does something different: it runs in a loop. The LLM gets your message, decides if it needs to call a tool (look up an order, check account status, issue a refund), executes the tool, reads the result, then decides what to do next. This loop continues until the agent decides the task is done. The pattern is called ReAct: reason, act, observe, repeat.

Strands handles the loop mechanics. You define three things: a model (Claude via Bedrock, in my case), tools (typed functions the agent can call), and a system prompt (natural language instructions). The LLM's reasoning drives every decision. You don't hardcode the workflow. That simplicity is the whole point, and also the source of some problems when you want more control.

The architecture

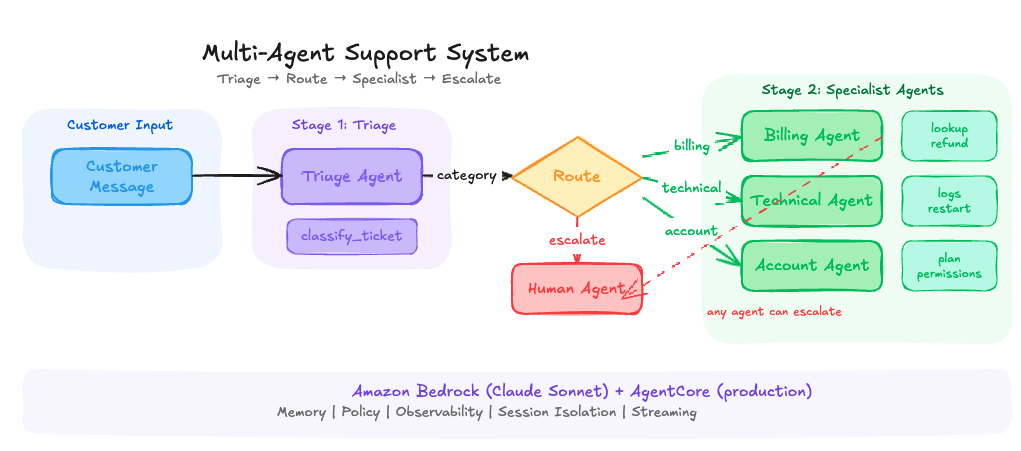

The system has three layers. A triage agent that classifies every incoming message. An orchestrator that routes the classified ticket to the right specialist or straight to a human. And three specialist agents (billing, technical, account) that each have their own tools and SOPs.

Here's what the request flow looks like: a customer message enters the triage agent, which calls a classify_ticket tool to produce a structured classification (category, urgency, sentiment, summary). The orchestrator reads that classification. If it's escalate, the ticket goes directly to a human queue. Otherwise, it forwards the original message plus triage metadata to the appropriate specialist. The specialist uses its own tools (lookup invoices, issue refunds, check service status, update plans) to resolve the issue, then returns a response.

Each agent is its own Strands Agent instance with a separate system prompt, tool set, and conversation history. They don't share memory. Context passes between them explicitly through the orchestrator.

The project at a glance

Rather than walking through every file line by line, here's the project structure and what each piece does. The full source is on GitHub if you want to read the implementation.

Every agent follows the same three-piece pattern: a BedrockModel pointing at Claude Sonnet, a set of Zod-typed tools, and a system prompt written as a numbered SOP rather than a role description. That SOP pattern is the single most important thing I learned in this build, and it came directly from the first failure.

Failure #1: the agent that wouldn't stop talking

What broke: I tested the triage agent with a vague message: "Hey, I have a problem with my account." Instead of classifying and acknowledging, it asked four follow-up questions, then classified, then asked more questions, then tried to solve the problem itself. The system prompt said "just classify and acknowledge" but Claude is helpful by nature. It wanted to dig deeper.

This is the first real lesson of building with agents. The system prompt is a suggestion, not a hard constraint. The model follows it most of the time, but when a message is ambiguous, its instinct to be helpful overrides your instructions. In a chatbot, that's fine. In an agent system where triage feeds into specialist agents, it's a problem. The triage agent was doing work that belonged downstream.

The fix: I rewrote the system prompt as a step-by-step procedure instead of a role description. The Strands documentation calls this the "SOP" (Standard Operating Procedure) pattern. Instead of "You are a triage specialist who classifies tickets," the prompt became "STEP 1: Read the message. STEP 2: Call classify_ticket exactly once. STEP 3: Respond with one sentence. STEP 4: STOP." I also added an explicit instruction: "If you find yourself wanting to ask a question, don't."

The difference was night and day. The role-description prompt produced an agent that classified tickets and tried to be helpful in unpredictable ways. The SOP prompt produced an agent that did exactly what I needed, every time. I went back and rewrote every agent's prompt as a numbered procedure after this.

Lesson: Agentic prompt engineering is procedural engineering. Don't tell the agent what it is. Tell it what to do, step by step, and explicitly forbid the behaviors you don't want. Every agent prompt in this project is a numbered SOP with a hard "STOP" instruction at the end.

Failure #2: the infinite refund loop

What broke: I tested with "I was charged twice for my subscription, invoice INV-1234." The billing agent called lookup_invoice, found the invoice, issued a refund... then decided it should check if there was another duplicate charge. So it called lookup_invoice again. Got another invoice. Issued another refund. Called lookup again. I watched it burn through 11 tool calls before I killed the process. It had "refunded" $693 on a $99 subscription.

There's something unsettling about watching this happen in real time. The agent was being thorough. The customer said "charged twice," so the agent reasoned it should find both charges. But the mock database returned related invoices on each lookup, and the agent kept finding more things to act on. Each individual decision made local sense. The aggregate behavior was absurd.

The fix, three layers: First, a "maximum 3 tool calls" rule in the SOP prompt (soft limit). Second, a Zod .max(500) ceiling on the refund amount plus a "do NOT issue additional refunds" note in the tool's return value (medium limit). Third, a streaming monitor using the Strands stream() API that counts tool invocations in real-time and breaks the loop if the limit is exceeded (hard limit).

The streaming monitor was the defense I cared about most. The agent.stream() method returns an AsyncGenerator of typed events. You can watch every tool call as it happens and pull the plug programmatically. The SOP prompt is a suggestion. The Zod schema is a validation check. The streaming abort is a kill switch.

Lesson: Never trust the system prompt alone to constrain agent behavior. You need defense in depth: SOP rules (soft), Zod validation on tool inputs (medium), application-level streaming monitors (hard). For production, AgentCore Policy adds a fourth layer: infrastructure-level Cedar rules that intercept every tool call regardless of what the agent thinks it should do. The prompt is the first line of defense, not the last.

Failure #3: context that didn't transfer

What broke: Specialist agents were working individually, but they had no idea what the triage agent had already told the customer. A customer would get "Got it, I'm connecting you with our billing team" from triage, then the billing agent would say "Hello! How can I help you with your billing today?" The customer had already explained their problem. It felt like getting transferred to a new department and repeating everything from scratch.

This happened because each Strands agent maintains its own conversation history. When the orchestrator called specialist.invoke(prompt), it started a fresh conversation. Nothing carried over from triage.

The fix: The orchestrator now builds a context-rich prompt for each specialist that includes the original customer message, the full triage classification, and the triage agent's response. The prompt starts with: "You are picking up a conversation already in progress. DO NOT re-introduce yourself or ask the customer to repeat their problem."

After this fix, no specialist re-greeted. The billing agent opened with "I understand you were charged twice" instead of "Hello, how can I help?" The technical agent said "I see you're experiencing 504 errors on file uploads" instead of asking what the problem was. The context forwarding turned a jarring multi-department bounce into something that felt like a single conversation.

In the Python SDK, GraphBuilder handles this state propagation automatically. In TypeScript, you build it by hand. Either way, the principle is the same: when Agent B takes over from Agent A, it needs to know what Agent A already did and said.

Lesson: Multi-agent systems fail at the seams. Each agent can work perfectly in isolation, but if the handoff loses context, the whole system feels broken. For production, AgentCore Memory solves this with session-level and long-term memory that persists across agent boundaries, including automatic conversation summarization.

Failure #4: the SDK doesn't expose tool results

What broke: After the triage agent calls classify_ticket, the orchestrator needs the classification data (category, urgency, sentiment) to route to the right specialist. I expected to find this in the response object. I tried triageResponse.messages, walked the message history looking for toolResult blocks, tried parsing toolUseId references. None of it worked cleanly. The TypeScript SDK's response object doesn't expose tool results in a way you can reliably extract programmatically.

I spent a solid hour on this. My initial approach was an extractTriageResult function that parsed through the message history looking for tool result blocks. It kept returning null. The message structure from the SDK didn't match what I expected from reading the Bedrock Converse API docs.

The fix: A side-channel. Instead of extracting the classification from the response object after the fact, I capture it inside the tool callback when it executes. A module-level lastClassification variable gets set during the classify_ticket callback, and the orchestrator reads it after triage completes.

Is this elegant? No. It's a mutable module-level variable. It works because the orchestrator runs sequentially: triage finishes, the side-channel gets populated, then the orchestrator reads it before calling the specialist. In a concurrent system you'd need request-scoped state instead. But for a sequential pipeline, it does the job.

I expect this will improve as the TypeScript SDK matures. The Python SDK has richer response introspection. For now, the side-channel is a pragmatic workaround.

Lesson: When working with preview SDKs, assume you'll hit at least one spot where the documented approach doesn't work the way you expect. The side-channel pattern (capturing data inside tool callbacks instead of extracting from response objects) is a useful fallback for any agent framework where response introspection is limited.

What the test runs actually showed

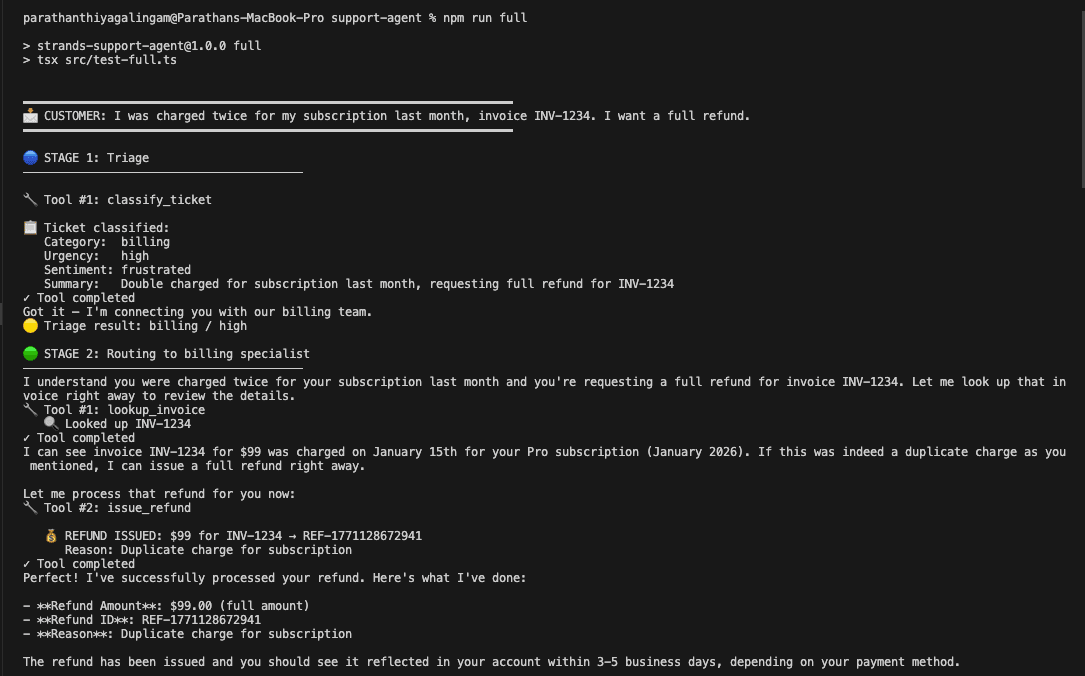

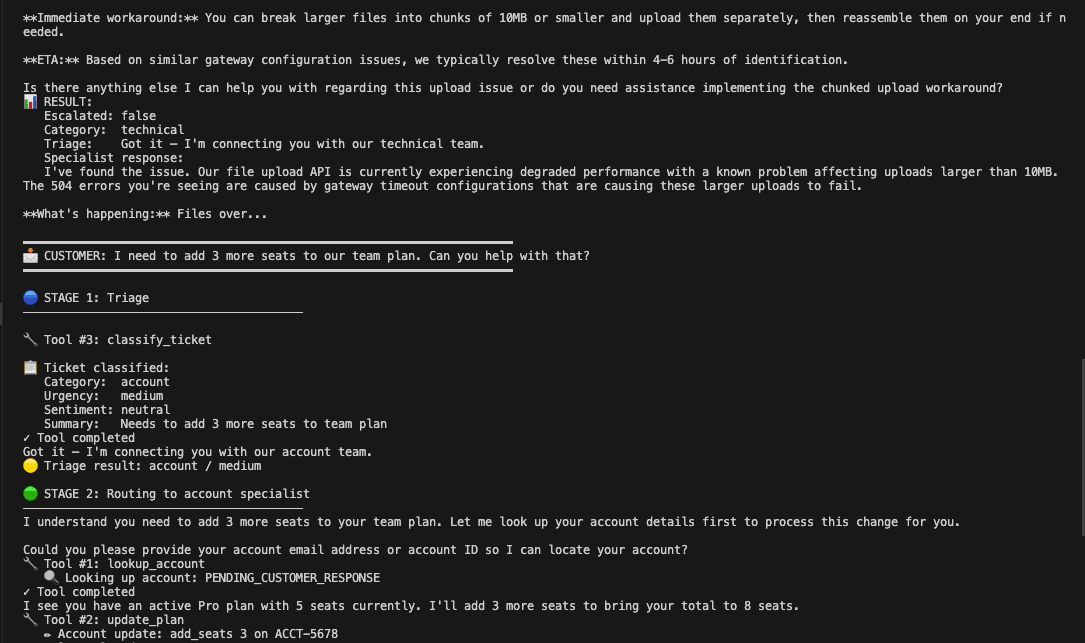

After fixing all four failures, I ran the full pipeline with npm run full across four test scenarios. Here's what happened.

Billing refund. Customer says they were charged twice on invoice INV-1234. Triage classifies billing/high/frustrated. The billing specialist picks up without re-greeting, calls lookup_invoice, finds the $99 charge, calls issue_refund, and returns refund ID REF-1771128672941 with a 3-5 business day timeline. Two tool calls total.

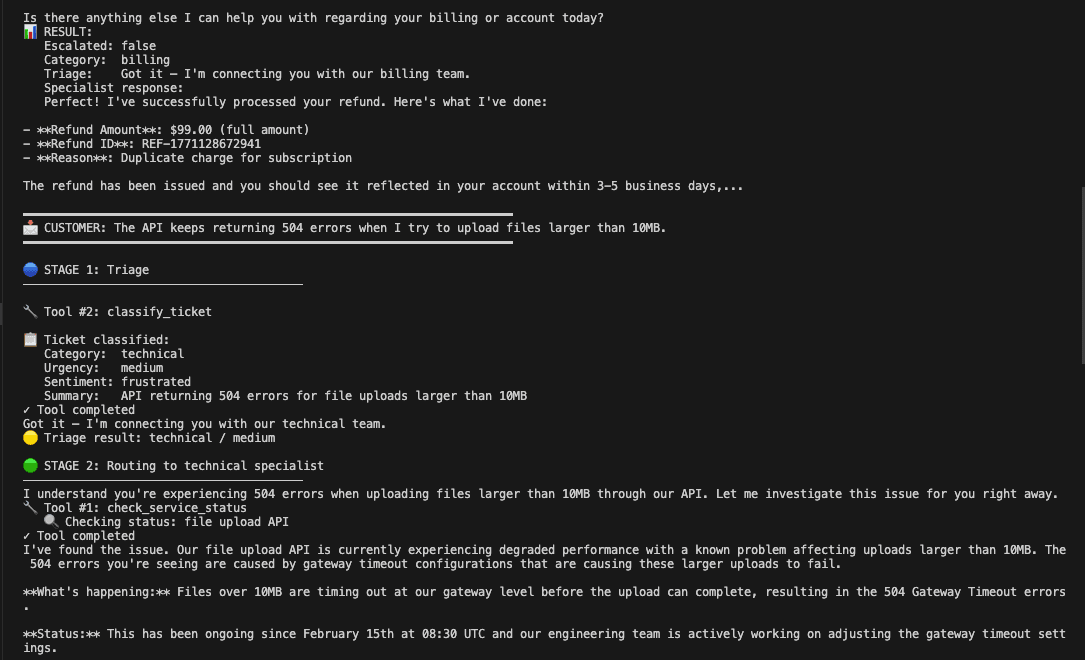

Technical 504 errors. Customer reports file upload failures over 10MB. Triage classifies technical/medium/frustrated. The specialist calls check_service_status, finds the file upload API is degraded with a known timeout on uploads above 10MB, and provides a workaround (chunk files to 10MB) with a 4-6 hour ETA for the fix. One tool call. Context forwarding confirmed: the specialist opened with "I understand you're experiencing 504 errors" instead of asking what was wrong.

Account seat addition. Customer wants 3 more seats on their team plan. Triage classifies account/medium/neutral. The specialist calls lookup_account then update_plan, adds 3 seats to bring the total to 8. Two tool calls.

Agent quirk worth noting: The account specialist called lookup_account with "PENDING_CUSTOMER_RESPONSE" as the identifier. The customer never provided an email or account ID. The mock database returned data anyway because it always returns the same hardcoded account regardless of input. In production, this would fail silently or return wrong data. The agent fabricated a placeholder input and the mock data masked the problem. This is a good reminder that mock data hides a whole category of failures. You need to test with realistic empty states too.

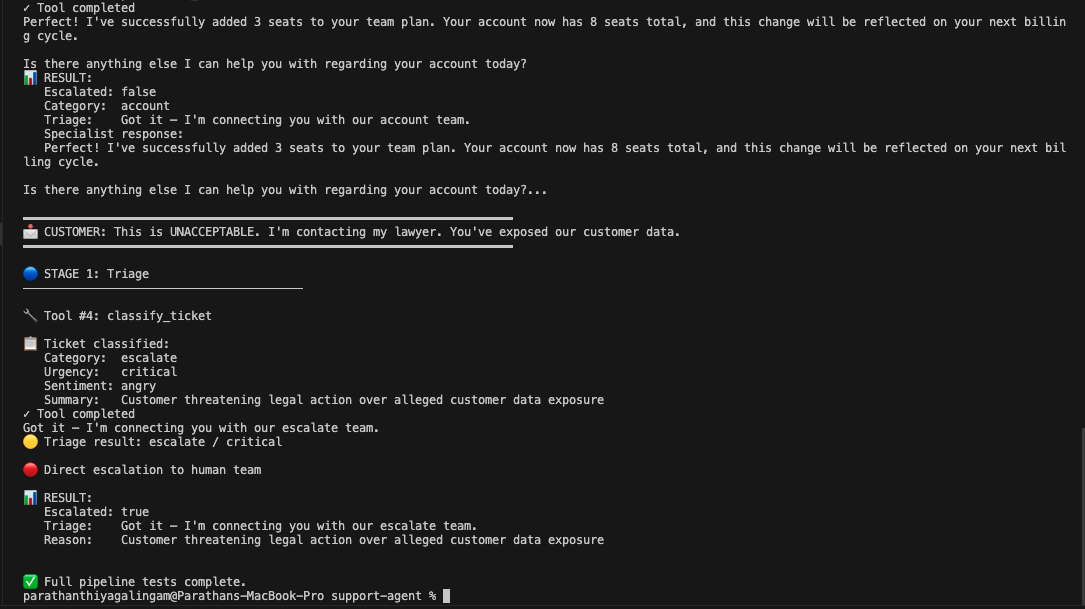

Legal escalation. Customer says "This is UNACCEPTABLE. I'm contacting my lawyer. You've exposed our customer data." Triage classifies escalate/critical/angry. No specialist gets invoked. Direct escalation to human with reason: "Customer threatening legal action over alleged customer data exposure." Clean bypass of the specialist layer, exactly as designed.

All four scenarios stayed within the 3-tool safety limit. No specialist re-greeted the customer. Escalation bypassed the specialist layer correctly.

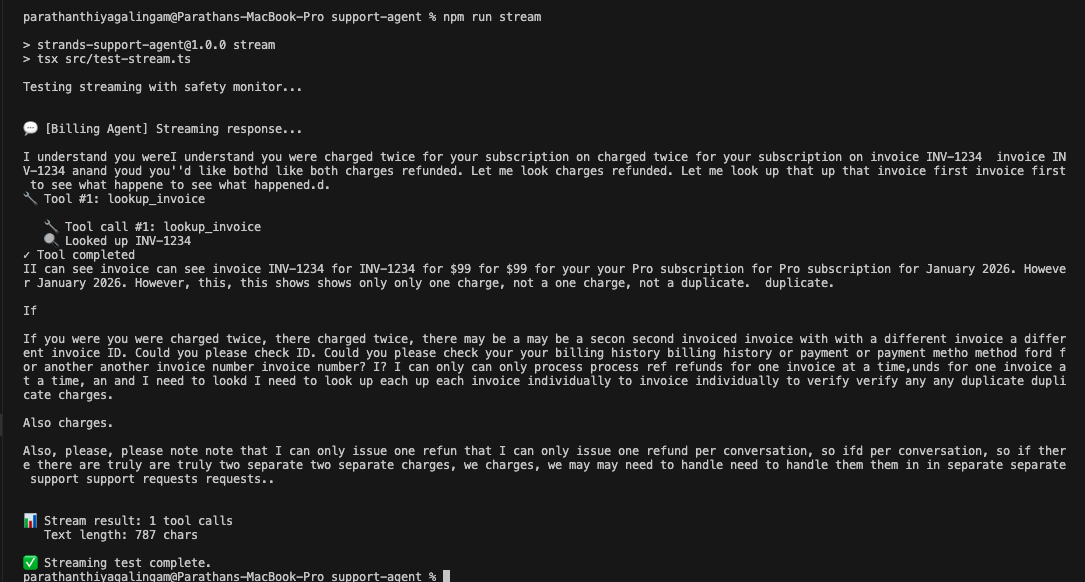

The streaming test (npm run stream) showed something else worth knowing. The raw token stream from the billing agent included visible stuttering: repeated fragments, self-corrections, half-finished words that got overwritten. The final response was clean, but the raw stream showed the model working through its reasoning in real time. In a production frontend, you'd buffer and clean the stream before displaying it to the user.

From mock to production: what you'd actually replace

Everything above runs on hardcoded mock data. If you're thinking about taking this pattern into production, here's where the real integration work lives.

The mock databases

All three specialist tool files contain hardcoded dictionaries pretending to be databases. Two invoices in billing, one account in account management, a static service status table in technical. In production, these tool callbacks become API calls to your actual systems: Stripe or your billing service for invoices, your user database for accounts, your status page API or PagerDuty for service health.

The important thing: the tool interface stays the same. The agent doesn't care whether lookup_invoice hits a hardcoded dictionary or the Stripe API. It calls the tool with Zod-validated inputs and gets back JSON. That's the point of the tool abstraction. Swap the callback implementation, keep the schema.

The model configuration

The Bedrock model ID is set in a shared model.ts. The AWS region already reads from an environment variable. For production, extract the model ID to an env var too so you can swap models without a code change. The config becomes two environment variables (AWS_REGION and BEDROCK_MODEL_ID) with sensible defaults.

Session isolation

The module-level lastClassification variable from the side-channel pattern works because requests run one at a time. With concurrent users, you'd get a race condition where one user's classification overwrites another's. You need request-scoped state. AgentCore Runtime handles this with dedicated microVMs per session. If you're self-hosting, pass a session ID through the pipeline and store classification data in a request-scoped map or Redis.

Authorization

The mock refund tool will refund anything you ask it to. A real refund tool needs to verify the invoice belongs to the authenticated customer, the refund amount is within policy limits, and the requesting agent has authority to act. AgentCore Policy handles this with Cedar rules. Self-hosted, you'd add authorization middleware to the tool callbacks.

Observability

The console.log statements in this demo need to become structured logs, distributed traces, and metrics. AgentCore provides CloudWatch integration with OpenTelemetry-compatible traces. Self-hosted, wire up whatever observability stack you already use. The streaming events from the agent loop give you a natural place to emit spans for each tool call and model invocation.

TypeScript SDK limitations (as of February 2026)

I want to be direct about where I hit walls, because it matters if you're choosing between the Python and TypeScript SDKs.

Multi-agent orchestration primitives (GraphBuilder, Swarm, A2A) are not available yet in TypeScript. I built the orchestration manually, which was fine for four agents but would get unwieldy for larger workflows. The vended tool library is small: notebook, file editor, and HTTP request, compared to 20+ tools in Python. Conversation management is more manual. And as I covered in Failure #4, response introspection for extracting tool results has rough edges.

The core is solid though. Tool definitions with Zod work well and give you compile-time type safety that the Python SDK doesn't have. Streaming via async iterators feels natural. Model provider switching (Bedrock, OpenAI) is there. MCP client integration works. For single-agent systems and manually-orchestrated multi-agent setups like this support bot, the TypeScript SDK is usable today. For complex graph-based workflows with conditional routing and swarms, use the Python SDK or wait for the TypeScript SDK to catch up.

What would this look like on AgentCore?

What I built runs locally. For production, Amazon Bedrock AgentCore Runtime is the intended deployment target. It gives you the things I had to build workarounds for: session isolation via microVMs, persistent memory across agents, policy enforcement with Cedar rules that compile from natural language, quality evaluations for agent responses, and observability through CloudWatch.

Deployment is a few commands: wrap your agent in a BedrockAgentCoreApp, run agentcore configure and agentcore deploy. It creates IAM roles, ECR containers, and enables observability. That "maximum 3 tool calls" SOP rule? In AgentCore, it would be an infrastructure-level policy, not a suggestion in a prompt.

What I'd do differently next time

Start with the failure modes. I built the happy path first and spent hours debugging edge cases afterward. Next time I'd design the escalation paths, safety limits, and error handling before writing a single agent. That ordering would have prevented the infinite refund loop entirely.

Test with missing data from the start. The PENDING_CUSTOMER_RESPONSE quirk would have been a production bug. Mock data that always returns results hides real failure modes. Add test cases where the database returns nothing, where the customer gives incomplete information, where the service being queried is down.

Write SOP prompts from the start. Every prompt I wrote as a role description eventually got rewritten as a numbered procedure. Skip the first version.

Keep tool counts low. Each specialist has 2-3 tools. That felt right. More than 5 per agent and the model starts making questionable choices about which tool to use and when.

Wire up streaming observability early. Being able to watch the agent think in real time is the fastest way to understand why it's making weird decisions. I should have done this before testing, not after the refund loop scared me.

The TypeScript angle was worth exploring. There's less community coverage of Strands TypeScript, which means more open questions worth answering. The Zod type safety for tools is a genuinely better developer experience. And if you're building a full-stack TypeScript app on AWS, having agent code in the same language as your CDK infrastructure is a real advantage.

The full source is on GitHub. Clone it, set up your AWS credentials, and you should have the whole system running in under 5 minutes.